A Mountain Warning Sung in Plain Truth, Where Tradition Speaks Softly but Carries the Weight of Experience

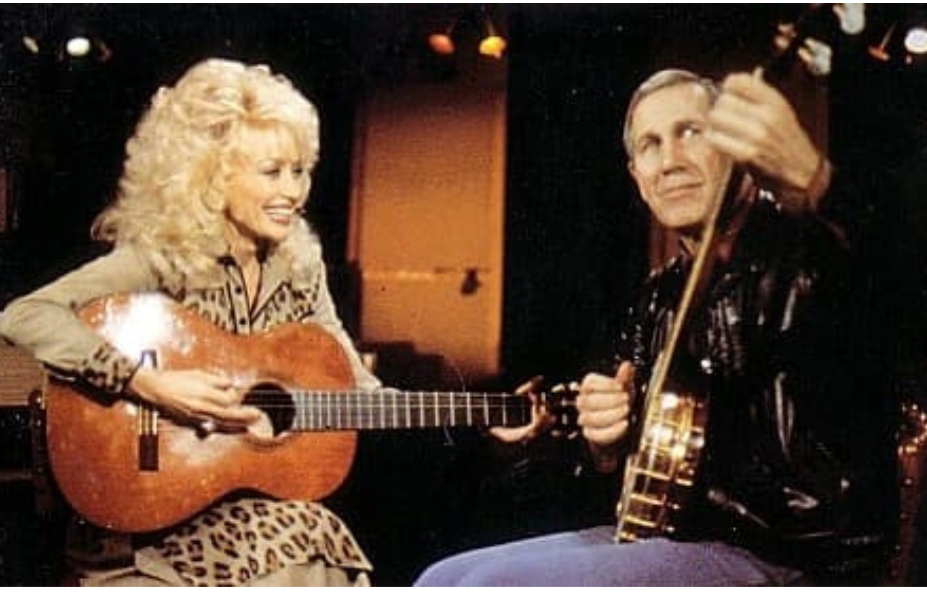

“Black Smoke’s a-Risin’”, recorded by Dolly Parton with Chet Atkins on banjo, is not a song that announces itself loudly. Instead, it arrives the way its title suggests—slowly, steadily, and with quiet inevitability. Released in 1964 on Dolly’s early album The Fabulous Country Music Sound of Dolly Parton, the recording did not make a major impact on the national charts, but its significance lies far beyond chart positions. It represents a meeting point of tradition, mentorship, and moral storytelling at a crucial moment in Dolly Parton’s artistic formation.

At the time, Dolly Parton was still at the beginning of her recording career, finding her voice within the framework of traditional country and Appalachian music. Chet Atkins, already an established giant and a guiding force behind the Nashville Sound, played banjo on the track—an inspired and symbolic choice. The banjo roots the song firmly in mountain tradition, resisting polish and reminding the listener that this story comes from older ground, shaped by experience rather than fashion.

The song itself is a traditional Appalachian murder ballad, part of a long lineage of folk songs that functioned as both warning and remembrance. These were songs meant not only to entertain, but to instruct—to pass down hard-earned lessons in communities where stories carried weight. “Black Smoke’s a-Risin’” belongs to that tradition fully. Its narrative is stark, its imagery vivid, and its message unmistakable: actions leave traces, and truth eventually rises, no matter how deeply it is buried.

From the opening lines, the image of black smoke becomes a powerful metaphor. Smoke signals fire, destruction, and consequence. It cannot be hidden for long. In the world of this song, guilt announces itself. Justice may arrive slowly, but it does arrive. There is no sensationalism in how the story is told—only inevitability.

Dolly Parton’s vocal performance is especially striking given her age at the time. She sings with clarity and restraint, resisting dramatization. There is no attempt to soften the song’s darkness, nor to exaggerate its moral weight. Her voice carries a calm authority, suggesting someone who understands that the story does not need embellishment. This directness would become one of her defining traits in later decades.

Chet Atkins’ banjo playing deserves particular attention. Known primarily for his guitar work, Atkins uses the banjo here not as a showpiece, but as a narrative tool. His playing is sparse, rhythmic, and deeply rooted. The banjo does not decorate the song—it underlines it. Each phrase reinforces the sense of motion, of events already set in motion and moving toward their end.

Musically, the arrangement is deliberately restrained. There are no sweeping harmonies, no dramatic crescendos. The focus remains on the story. This restraint reflects an older philosophy of country and folk music, where the song’s purpose was clarity rather than spectacle. Everything serves the narrative.

Within Dolly Parton’s early discography, “Black Smoke’s a-Risin’” stands as a clear statement of artistic direction. Long before her crossover success, before pop stardom and global recognition, she demonstrated a deep respect for traditional storytelling. This was not nostalgia—it was inheritance. The song reflects the musical world she came from, shaped by mountain ballads, moral tales, and the belief that music should tell the truth plainly.

For Chet Atkins, the recording reflects another side of his legacy. Beyond shaping commercial country music, he remained deeply connected to its roots. His presence on this track is subtle but profound—a quiet endorsement of a young artist who understood where the music came from.

Listening to “Black Smoke’s a-Risin’” today feels like opening an old book whose pages are worn but whose message remains intact. The language is simple. The warning is clear. The emotions are not exaggerated, yet they linger.

This is not a song about hope or redemption. It is a song about consequence. About the certainty that what is done in darkness eventually reveals itself. And in that sense, it remains timeless.

In the shared space between Dolly Parton’s clear young voice and Chet Atkins’ grounded banjo, “Black Smoke’s a-Risin’” preserves a moment when country music still leaned heavily on its oldest responsibility: to remember, to warn, and to tell the truth without apology.