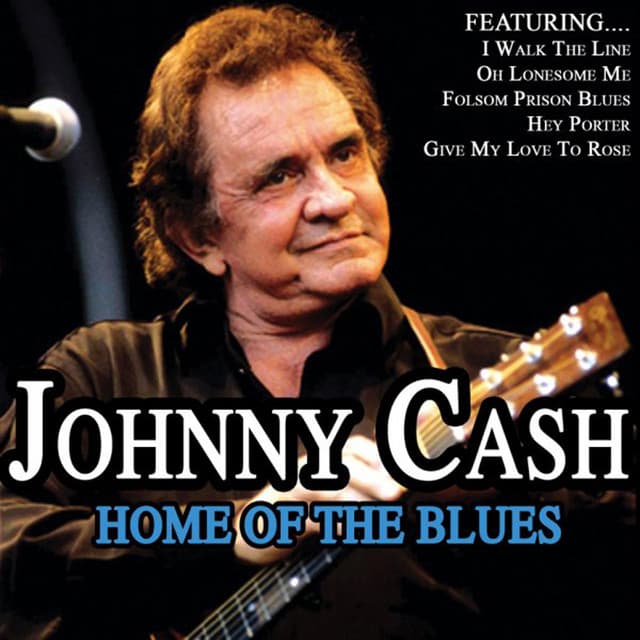

“Home of the Blues” a lonely walk through sorrow’s doorway, voiced by a man who carried the weight of loss

When Home of the Blues plays, you feel the door to sorrow gently swing open a slow, quiet entrance into heartache, regret, and the longing for a home no longer warm.

Back in August 1957, the legendary Johnny Cash released Home of the Blues as a single (with “Give My Love to Rose” on the B-side), recorded just a month earlier in Memphis on July 1, 1957. By the time the song began to traverse the airwaves, it had already been layered with the dust of memory and pain a story born from Cash’s own troubled childhood.

On the charts, Home of the Blues climbed to #3 on the U.S. Billboard Country chart, and even nudged the pop world, reaching #88 on the pop listing. It was not the number-one smash that some of his later hits became yet in its modest success lies the seed of something deeper: a song that spoke not to mass celebration, but to quiet desperation and universal longing.

What gives Home of the Blues its haunting power is its bare-bones truth. Johnny Cash, along with co-writers Lillie McAlpin and Glenn Douglas Tubb, fashioned a song that doesn’t gild sorrow it simply lays it bare. In those opening lines “Just around the corner there’s heartache / Down the street that losers use” you don’t just hear a song: you smell the stale air of broken dreams, you feel the empty chair, you sense footsteps echoing down a lonely hallway.

Cash’s recording is spare: a simple guitar, his deep, resonant voice, and the silence that fills what isn’t sung. No lush orchestration, no glimmering chorus just a man and his past, laid bare in sound. That minimalism became Cash’s signature: the strength of his music lay not in what was added, but in what he chose to leave out. In this song it serves the story perfectly: sorrow lives in emptiness, and longing thrives in silence.

The context behind the song deepens its poignancy. Cash drew from his own upbringing a childhood stained by loss, hardship, and roots in sorrow. The “home of the blues” he sings about isn’t a place of comfort, but a metaphorical house built out of tears and memories, where the walls echo with regrets and the songs are born from broken hearts.

When the record first spun on radios and juke-boxes, listeners may have heard a country tune. But to many who had known loss loss of love, loss of home, loss of innocence Home of the Blues became something more. It was a mirror, showing their ache, their solitude, their dark nights. It wasn’t meant to lift the soul; it was meant to reach inside it, tug gently at the scars, and name what many felt but could not speak.

In the arc of Johnny Cash’s catalog, this song holds a unique place. Before the swagger of rebellion, before the outlaw gravitas, there was this a humble ballad of pain and memory. Its inclusion on the album Sings the Songs That Made Him Famous anchored that record not just as a collection of hits, but as a tapestry of human experience: hope, heartache, redemption all woven with the same honest thread.

Today, listening to Home of the Blues is like walking through a dim corridor of the past gentle light at the end, but heavy footsteps echoing with the weight of time. It reminds us that behind every melody there might be a story. A story not of victory, but of survival.

For those who once knew loneliness on a porch at midnight, or grief in empty rooms, or quiet sadness in a passing glance this song remains a companion. It doesn’t offer solace. It doesn’t promise healing. It simply acknowledges pain. And sometimes, that acknowledgment is the most human gift music can give.

In an age where songs shout to be heard, Home of the Blues whispers inviting you to listen, to remember, and perhaps to feel once more what it meant to be alive, wounded, and still longing for home.