A Tragic Song of Fame and Regret, Where Success Arrives Too Late to Save the Heart

When Elvis Presley recorded “Long Black Limousine,” he gave voice to one of the darkest truths in American popular music: that fame, wealth, and recognition often arrive only after the cost has already been paid. This is not a song of glory. It is a lament. A warning. And in Elvis’s hands, it becomes painfully prophetic.

“Long Black Limousine” was written by Vern Stovall and Bobby George in the late 1950s. The song was first recorded in 1960 by Wynn Stewart, whose version reached No. 9 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart. Its story a poor family losing a son who left home chasing success, only to return in death was already powerful within the country tradition. But it was Elvis Presley’s interpretation, recorded in January 1969, that gave the song its most haunting and enduring form.

Elvis’s version was released on the landmark album From Elvis in Memphis (1969), a record that marked his full artistic rebirth. The album peaked at No. 13 on the Billboard Top LPs chart and is widely regarded as one of the finest works of his career. While “Long Black Limousine” was not released as a single and therefore did not chart independently, its emotional weight has only grown with time.

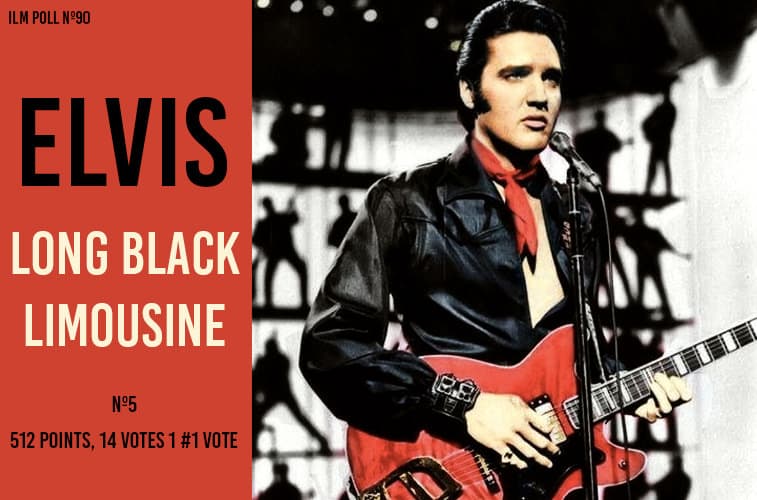

By 1969, Elvis was no longer the young man bursting onto the scene with raw rebellion. He was a seasoned artist carrying years of pressure, isolation, and personal struggle. That context changes everything about this recording. When Elvis sings “Long black limousine / shining like a raven’s wing,” he does not sound like a storyteller observing tragedy from afar. He sounds like someone who understands it intimately.

Musically, the arrangement is restrained and somber. The slow tempo, gentle rhythm section, and mournful instrumentation create a sense of inevitability. There is no dramatic build, no release. The song moves forward like a funeral procession steady, heavy, and impossible to stop. This restraint allows Elvis’s voice to carry the full emotional burden.

Vocally, Elvis delivers one of his most controlled and sorrowful performances. He avoids melodrama entirely. His phrasing is careful, almost resigned. Each line feels weighed down by regret, not anger. The tragedy in “Long Black Limousine” is not sudden; it is cumulative. It comes from distance distance between parent and child, between dreams and reality, between public success and private loss.

The story at the heart of the song is simple and devastating. A young man leaves home with nothing but ambition. Years pass. The family hears nothing. When he finally returns, it is in a long black limousine not as a triumph, but as a funeral. The wealth he gained means nothing now. It cannot repair the silence. It cannot buy back time.

In the context of Elvis’s life, this narrative takes on an almost unbearable resonance. Though recorded years before his own death, the song now feels eerily reflective. Elvis himself would become a global icon whose private struggles were hidden behind luxury, headlines, and spectacle. That is why this performance continues to feel less like fiction and more like confession.

“Long Black Limousine” also fits seamlessly into the broader themes of From Elvis in Memphis, an album filled with songs about adulthood, consequence, and emotional reckoning. This was Elvis confronting material that demanded honesty rather than charm. And he rose to it with quiet dignity.

The deeper meaning of the song lies in its moral clarity. It does not condemn ambition, nor does it romanticize poverty. Instead, it mourns the cost of forgetting where one comes from. It asks listeners to consider what success is worth if it requires the sacrifice of connection, presence, and love.

Today, “Long Black Limousine” stands as one of Elvis Presley’s most overlooked masterpieces. It lacks the radio-friendly hooks of his biggest hits, but it offers something far rarer: truth delivered without ornament. It is the sound of an artist singing not to impress, but to understand.

Long after the final note fades, the image remains the limousine passing slowly, silently, carrying not victory, but regret. And in that image, Elvis leaves us with one of his most sobering lessons: that applause fades, riches vanish, but the ache of absence endures.