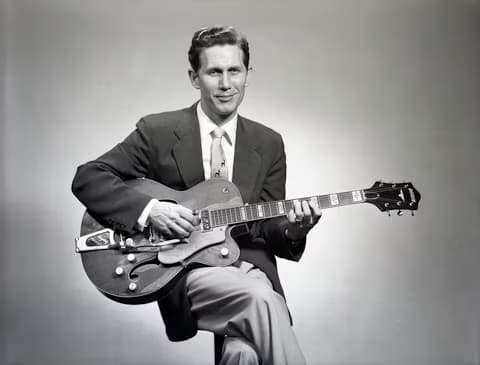

A joyful celebration of precision, playfulness, and the enduring sparkle of American guitar tradition

When Chet Atkins recorded “Alabama Jubilee,” he wasn’t simply revisiting a familiar tune—he was reaffirming a lineage that stretches back to the earliest days of American popular music. Originally composed in 1915 by George L. Cobb and Jack Yellen, “Alabama Jubilee” had already lived many lives before Atkins touched it: as a ragtime favorite, a jazz standard, and a showpiece for instrumental virtuosity. In Atkins’ hands, however, the piece became something uniquely his elegant, controlled, and quietly exhilarating.

Atkins’ notable recordings of “Alabama Jubilee” appeared during the late 1950s and early 1960s, a period when his albums consistently ranked high on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart, even when individual instrumental tracks were not released as charting singles. This context matters. At a time when popular music was increasingly vocal-driven, Atkins continued to prove that instrumental storytelling could command attention, respect, and commercial success.

From the first notes, Atkins’ version announces its character with clarity. The melody dances—bright, quick-footed, and confident yet never feels rushed. His trademark fingerstyle technique allows bass, harmony, and melody to coexist seamlessly, creating the illusion of multiple musicians playing at once. This was always part of Atkins’ magic: complexity delivered with ease, difficulty disguised as comfort.

What distinguishes Chet Atkins’ “Alabama Jubilee” from earlier renditions is restraint. Many musicians approached the tune as a race, emphasizing speed and flash. Atkins, by contrast, emphasizes balance. Yes, the tempo is lively, and yes, the technical demands are formidable but nothing feels forced. Each phrase is articulated with care, every run lands exactly where it should. The joy of the performance lies not in spectacle, but in confidence born of mastery.

Historically, “Alabama Jubilee” was a song designed to lift spirits. Written during a time of rapid social change in early 20th-century America, it carried a sense of optimism and communal celebration. Atkins preserved that spirit while subtly reshaping it. His interpretation removes the song from the noisy dance halls of its origin and places it into a more reflective space still joyful, but polished, mature, and timeless.

This approach reflects Atkins’ broader role in shaping the Nashville Sound. While he is often remembered for smoothing the rough edges of country music, performances like “Alabama Jubilee” reveal another truth: Atkins never diluted tradition; he refined it. He understood that honoring the past did not require imitation it required understanding.

Musically, his tone is warm and rounded, free of aggression. The guitar sings rather than shouts. Even in the most technically demanding passages, Atkins leaves room for breath. Silence matters as much as sound. That sense of space allows the listener to follow the melody’s arc, to feel the natural rise and fall of the tune rather than being overwhelmed by it.

Emotionally, “Alabama Jubilee” carries a subtle nostalgia. Not the kind that mourns what is lost, but the kind that celebrates what endures. There is a smile in the music a quiet acknowledgment that joy, when carefully tended, can outlast fashion and trend. Atkins does not exaggerate that feeling; he trusts it to speak for itself.

Within Chet Atkins’ vast catalog, “Alabama Jubilee” stands as a reminder of his deep respect for American musical roots. Alongside his interpretations of folk songs, pop standards, and original compositions, this recording shows his ability to move effortlessly between eras without losing identity. He acts as a bridge connecting ragtime’s exuberance, country’s intimacy, and modern guitar’s precision.

Over the decades, guitarists across genres have studied Atkins’ version of “Alabama Jubilee” not just to learn the notes, but to understand the philosophy behind them. It teaches that true brilliance lies in clarity, that joy does not need exaggeration, and that tradition remains alive only when treated with care.

Today, Chet Atkins’ “Alabama Jubilee” continues to sparkle not because it is loud or dramatic, but because it is perfectly balanced. It reminds us that music can be joyful without being careless, virtuosic without being boastful, and timeless without standing still.

In that sense, the song becomes more than a performance. It becomes a quiet celebration of craftsmanship itself steady hands, clear mind, open heart and the enduring pleasure of hearing something done exactly right.