A Warm Guitar Glow on a Familiar Winter Melody, Where Tradition Meets Quiet Swing

When Chet Atkins recorded “Jingle Bell Rock” in the early 1990s, later released in 1993 on holiday compilations associated with his Christmas recordings, the gesture felt less like a seasonal novelty and more like a personal signature placed gently upon a well-worn tradition. The track did not appear on the Billboard charts, nor was it intended to compete with pop-oriented holiday releases. Its value lies elsewhere—in tone, restraint, and the unmistakable elegance of a guitarist who understood that less could often say far more.

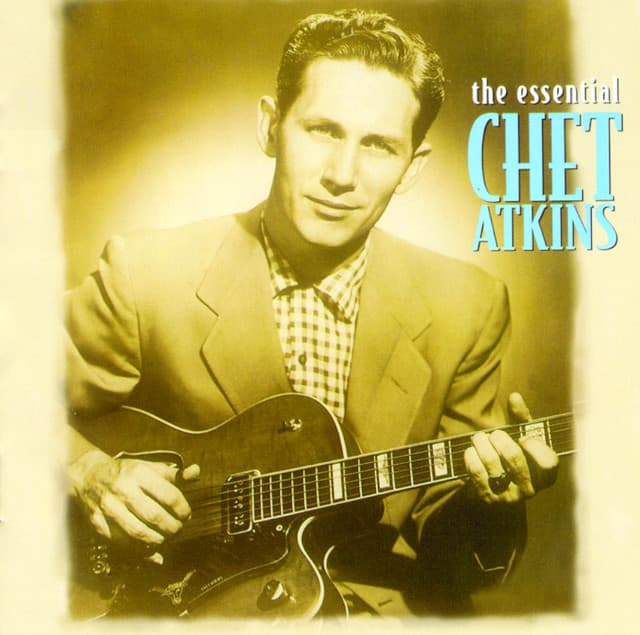

By the time this recording appeared, Chet Atkins was already universally acknowledged as “Mr. Guitar,” a central architect of the Nashville Sound and one of the most influential instrumentalists of the twentieth century. His career spanned decades, shaping country, pop, jazz, and even classical crossover recordings. A Christmas song in his hands was never going to be loud or theatrical. Instead, it would be thoughtful, polished, and quietly joyful.

Originally written by Joseph Carleton Beal and James Ross Boothe, “Jingle Bell Rock” first became a sensation in 1957 through Bobby Helms, blending holiday imagery with the rhythmic pulse of early rock ’n’ roll. Over the years, the song accumulated countless versions, many of them energetic, playful, and overtly nostalgic. Chet Atkins’ interpretation, however, takes a different path. It strips the song of lyrical cheer and reframes it as an instrumental conversation—one led by guitar rather than voice.

From the opening bars, Atkins’ tone is instantly recognizable. Clean, warm, and impeccably controlled, his guitar sings with a calm confidence. There is swing here, but it is subtle. The rhythm moves easily, never rushing, allowing the melody to breathe. Rather than announcing the holiday season, this version seems to welcome it quietly, like lights turned on softly in the evening.

What makes this rendition special is its balance between familiarity and individuality. The melody remains intact, respectful of the song’s identity, yet Atkins introduces gentle harmonic turns and rhythmic nuances that reflect his deep musical intelligence. Each phrase feels intentional, shaped by decades of experience rather than technical display. There is no need to impress; the mastery is already understood.

The arrangement reflects Atkins’ lifelong philosophy as a musician. He believed that technique should serve emotion, not dominate it. In “Jingle Bell Rock”, the guitar does not dazzle—it reassures. It carries a sense of comfort, of continuity, reminding the listener that traditions endure not because they are repeated loudly, but because they are treated with care.

Within the broader context of Chet Atkins’ Christmas recordings—stretching back to albums like Christmas with Chet Atkins (1961) and East Tennessee Christmas (1983)—this 1993-era recording feels like a late reflection rather than a festive announcement. It carries the calm of someone who has lived through many seasons, who no longer feels the need to decorate every moment, but understands the power of understatement.

Emotionally, the performance evokes warmth rather than excitement. It suggests winter evenings rather than crowded celebrations, memory rather than spectacle. The absence of lyrics allows space for personal reflection, letting the listener fill the melody with their own associations. In that silence, the song becomes intimate.

Though it never charted, “Jingle Bell Rock” as interpreted by Chet Atkins has quietly endured, circulating among listeners who appreciate craftsmanship over novelty. It stands as a reminder that holiday music need not shout to be meaningful. Sometimes, a gentle guitar line is enough to summon everything the season represents—comfort, familiarity, and a sense of home.

In the final years of his career, Atkins often played with an air of peaceful authority. This recording captures that spirit perfectly. It is not about reinventing a classic, nor about revisiting youth. It is about honoring a melody with dignity, allowing it to pass through experienced hands and emerge calmer, warmer, and somehow wiser.

In the end, Chet Atkins’ “Jingle Bell Rock” (1993) feels less like a seasonal performance and more like a quiet blessing—a reminder that the most lasting celebrations are often the ones spoken softly, carried by strings, and remembered long after the final note fades.