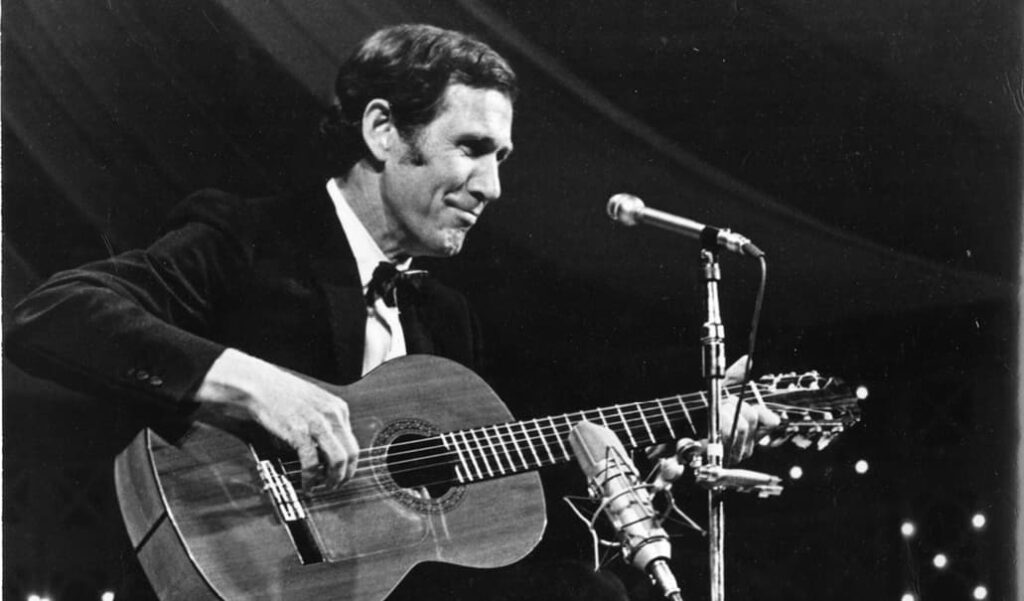

A playful dream in six strings, where early television captured the gentle wit and elegance of a guitar master

In the long and richly textured history of American popular music, Chet Atkins stands apart as a figure who reshaped the sound of the guitar without ever raising his voice. His 1954 television performance of “Mr. Sandman” is a small moment in duration, yet a revealing portrait of an artist whose influence would quietly ripple across decades. Though this rendition never appeared on the charts, its cultural value lies elsewhere — in how it reflects a turning point in music, media, and the art of understatement.

The song “Mr. Sandman” was written in 1954 by Pat Ballard and became an immediate sensation later that same year through The Chordettes, whose crisp, close-harmony version reached No. 1 on the Billboard Best Sellers in Stores chart. Their recording captured the postwar American mood: optimistic, lighthearted, and touched by novelty. It was a song that smiled easily, asking for romance not with urgency, but with charm.

Chet Atkins, however, approached the song from an entirely different angle. In his 1954 TV appearance, he stripped the lyrics away and let the guitar speak. What emerged was not a novelty tune, but a miniature study in tone, timing, and musical intelligence. Atkins transformed a vocal pop hit into a refined instrumental conversation, proving how adaptable — and how deep — popular material could be when placed in the right hands.

At this point in his career, Chet Atkins was already a respected guitarist and producer at RCA Victor, though his full legacy had yet to unfold. Television itself was still young, intimate, and experimental. Performances were not polished spectacles but shared moments, often broadcast live or with minimal rehearsal. In this environment, Atkins’ calm presence stood in quiet contrast to the novelty-driven energy of early TV entertainment.

Musically, his version of “Mr. Sandman” is deceptively simple. The melody remains instantly recognizable, but Atkins enriches it with subtle harmonic movement and his signature fingerstyle technique. His thumb maintains a steady rhythmic foundation while his fingers articulate the melody with a light, almost conversational touch. There is no flash for its own sake. Every note feels considered, unhurried, and purposeful.

What makes this performance especially striking is its sense of humor — not the exaggerated kind, but a gentle musical wit. Atkins allows the guitar to “sing,” echoing the playful spirit of the original lyrics without needing words. The pauses, the phrasing, the delicate bends all suggest a smile just beneath the surface. It is humor expressed through restraint, something Atkins mastered like few others.

Historically, this performance sits at a fascinating crossroads. The early 1950s marked a shift in American music, where country, pop, jazz, and emerging rock influences were beginning to overlap. Chet Atkins would soon become one of the key architects of the Nashville Sound, smoothing the edges of country music and bringing it closer to pop audiences without sacrificing musicianship. His “Mr. Sandman” performance already hints at that philosophy: accessibility paired with elegance.

Though this rendition did not chart and was never intended as a commercial release, it gained lasting recognition through broadcasts, archival footage, and the memories of those who witnessed it. It represents a time when musicians were trusted to simply play — to let their craft speak directly, without layers of production or spectacle.

Emotionally, the performance evokes a quieter nostalgia. It recalls an era when television felt personal, when music entered living rooms as a shared experience rather than background noise. Atkins’ relaxed posture and unassuming demeanor reinforce that feeling. He does not perform at the audience; he plays with them, inviting listeners into a moment of calm delight.

In retrospect, Chet Atkins’ “Mr. Sandman” (TV 1954) is less about the song itself and more about the philosophy behind it. It is a reminder that great musicianship does not demand attention — it earns it gently. Through six strings and a knowing sense of timing, Atkins turned a popular tune into something enduring.

Long after the charts have faded and television formats have changed, this performance remains a small but luminous example of how music, when treated with respect and imagination, can outlive its moment. And in that softly swinging melody, the Sandman still walks — not through dreams, but through memory.