A Quiet Goodbye at the Edge of the Microphone, Where Love, Loss, and Time Finally Stand Still

“He’ll Have to Go” holds a uniquely fragile place in the vast and complex legacy of Elvis Presley. Recorded in October 1976 at Graceland’s famed Jungle Room, the song is widely regarded as one of the final recordings Elvis ever made, and is often cited as the last song he recorded in a studio setting. Released posthumously in 1977 on the album Moody Blue, it arrived not as a chart-seeking single but as a quiet epilogue an unintended farewell whispered rather than proclaimed.

Originally written by Joe and Audrey Allison and made famous in 1959 by Jim Reeves, “He’ll Have to Go” was already a classic long before Elvis approached it. Reeves’ version famously reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 1 on the Country chart, becoming a benchmark for emotional restraint in popular music. Elvis, however, did not attempt to compete with that legacy. Instead, he transformed the song into something deeply personal less a performance, more a confession.

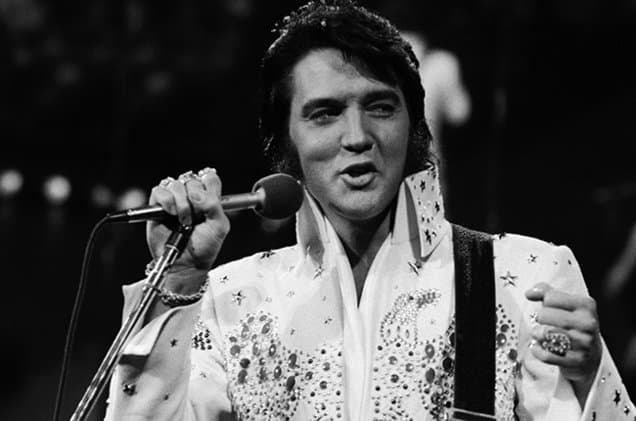

By late 1976, Elvis Presley was physically weakened and emotionally worn, yet artistically honest in a way that stripped away all illusion. His voice on “He’ll Have to Go” is lower, rougher, and profoundly intimate. Gone is the swagger of the 1950s, the cinematic grandeur of the 1960s, or even the commanding stage presence of the early Vegas years. What remains is a man alone with a microphone, leaning into each syllable as if aware that every word matters.

The song’s narrative is deceptively simple: a man overhears a woman on the telephone, realizes she belongs to someone else, and gently insists that if she truly wants him, “he’ll have to go.” In Elvis’ hands, those words take on a haunting resonance. The pauses feel longer. The silences speak louder. When he nearly whispers “put your lips a little closer to the phone,” it sounds less like seduction and more like longing filtered through resignation.

There was no commercial push behind the recording. When Moody Blue was released in July 1977, just weeks before Elvis’ passing, the album reached No. 3 on the Billboard 200 and No. 1 on the Country Albums chart, driven largely by public emotion and loyalty rather than radio strategy. “He’ll Have to Go” itself did not chart as a standalone single, but its significance was never measured in numbers. Its power lies in context.

The Jungle Room sessions were raw and unconventional. Elvis recorded at home, often late at night, surrounded by familiar walls rather than studio polish. These sessions produced songs filled with weariness, tenderness, and reflection—“Moody Blue,” “Way Down,” and “She Thinks I Still Care.” Among them, “He’ll Have to Go” stands apart for its stillness. It feels like the moment after the lights dim, when applause has faded and nothing is left to hide behind.

Listening today, it is impossible not to hear the echoes of Elvis’ own life in the song. The themes of distance, missed connection, and emotional honesty mirror a man who had spent years surrounded by people yet often felt profoundly alone. There is no self-pity here, only acceptance. The song does not beg for love—it acknowledges reality.

What makes this recording especially moving is its lack of finality. Elvis does not frame it as an ending. There is no grand statement, no farewell speech. Instead, he leaves us with a song about letting go, about recognizing when love belongs elsewhere. In doing so, he unknowingly offered one of the most human moments of his entire career.

“He’ll Have to Go” is not remembered as Elvis’ greatest vocal triumph, nor was it meant to be. It is remembered because it feels true. It captures a man at the end of a long road, still singing, still feeling, still reaching for connection through music.