A Stark Ballad of Pride, Pain, and Powerlessness, Where Love Collides with Wounded Masculinity

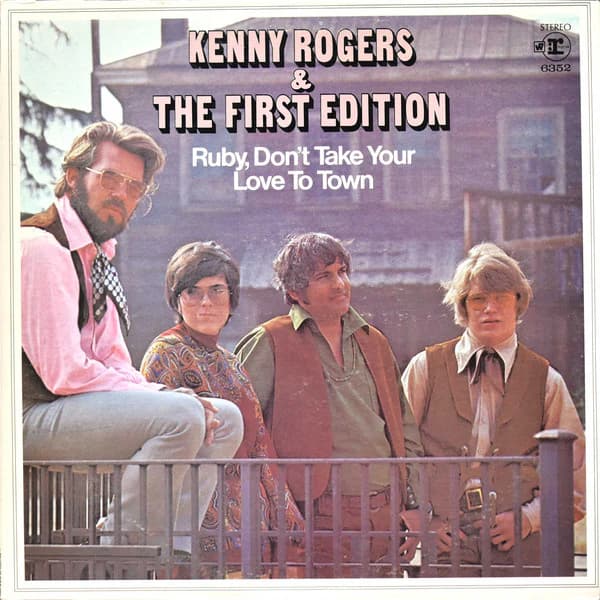

When Kenny Rogers & The First Edition released “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” in 1967, popular music was rarely this raw, this uncomfortable, or this honest. Issued as a single and later appearing on the album The First Edition (1968) before lending its name to the 1969 LP Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town, the song became an unexpected and unforgettable hit. It climbed to No. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100, reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, and topped the Adult Contemporary chart, an extraordinary crossover achievement for a song so emotionally severe.

Written by Mel Tillis, “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” was unlike almost anything else on radio at the time. It told its story from the perspective of a paralyzed man—widely interpreted as a wounded veteran—watching helplessly as his wife prepares to leave the house, dressed to attract another man. The narrator is trapped not only by his physical condition, but by pride, jealousy, and a crushing sense of inadequacy. This was not romance. This was confrontation.

What made the song so striking was its refusal to soften the truth. The narrator does not beg gently. He does not reflect calmly. He burns inwardly. His love is tangled with resentment, his devotion poisoned by fear of abandonment. In the final verse, the implication of violence—never fully stated, but unmistakably present—sent shockwaves through audiences. At a time when much of popular music avoided moral ambiguity, “Ruby” embraced it.

Kenny Rogers, still years away from his solo superstardom, delivered the vocal with chilling restraint. His voice is steady, almost conversational, which only deepens the song’s menace. He does not dramatize the anger; he lets it simmer. That choice turns the listener into a witness rather than a spectator. The performance feels disturbingly intimate, as if overhearing something that was never meant to be shared.

Musically, the arrangement is sparse and deliberate. The melody is simple, almost folk-like, allowing the lyrics to remain front and center. There is no emotional release in the music—no soaring chorus to relieve the tension. The song moves forward relentlessly, mirroring the narrator’s inability to escape his situation. Each verse tightens the emotional grip.

The cultural context of the late 1960s adds further depth to the song’s impact. Though the lyrics never explicitly mention war, many listeners connected the narrator’s paralysis to the growing presence of wounded veterans returning home. In that reading, “Ruby” becomes not just a personal tragedy, but a broader reflection on masculinity, loss of identity, and the invisible scars carried long after physical wounds.

The song’s success was both commercial and transformative. It established Kenny Rogers & The First Edition as artists willing to take risks, and it positioned Rogers as a compelling storyteller long before his solo career would define him as one of music’s great narrators of human complexity. Without “Ruby”, it is difficult to imagine later classics like “Lucille” or “The Gambler” carrying the same authority.

Yet the song has always been divisive. Some listeners were unsettled by its tone, troubled by its unresolved anger. Others recognized its bravery. “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” does not offer moral guidance. It does not excuse the narrator, nor does it condemn Ruby. Instead, it exposes the fragile intersection of love, pride, and desperation—and leaves judgment to the listener.

Over time, the song has aged into something more than controversy. It now stands as a landmark of narrative songwriting, proof that popular music can confront uncomfortable truths without losing its audience. Its power lies in its honesty: love is not always gentle, and pain does not always produce wisdom.

Listening to “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” today remains a sobering experience. It is not a song one casually hums. It demands attention, reflection, and emotional courage. In the long arc of Kenny Rogers’ career, it marks the moment when storytelling became destiny.

And long after the final line fades, the silence it leaves behind is its true legacy—a reminder that some songs endure not because they comfort us, but because they force us to look directly at what we would rather avoid.