A Voice from the Jukebox After Midnight: Loneliness, Honesty, and the Birth of Modern Country Blues

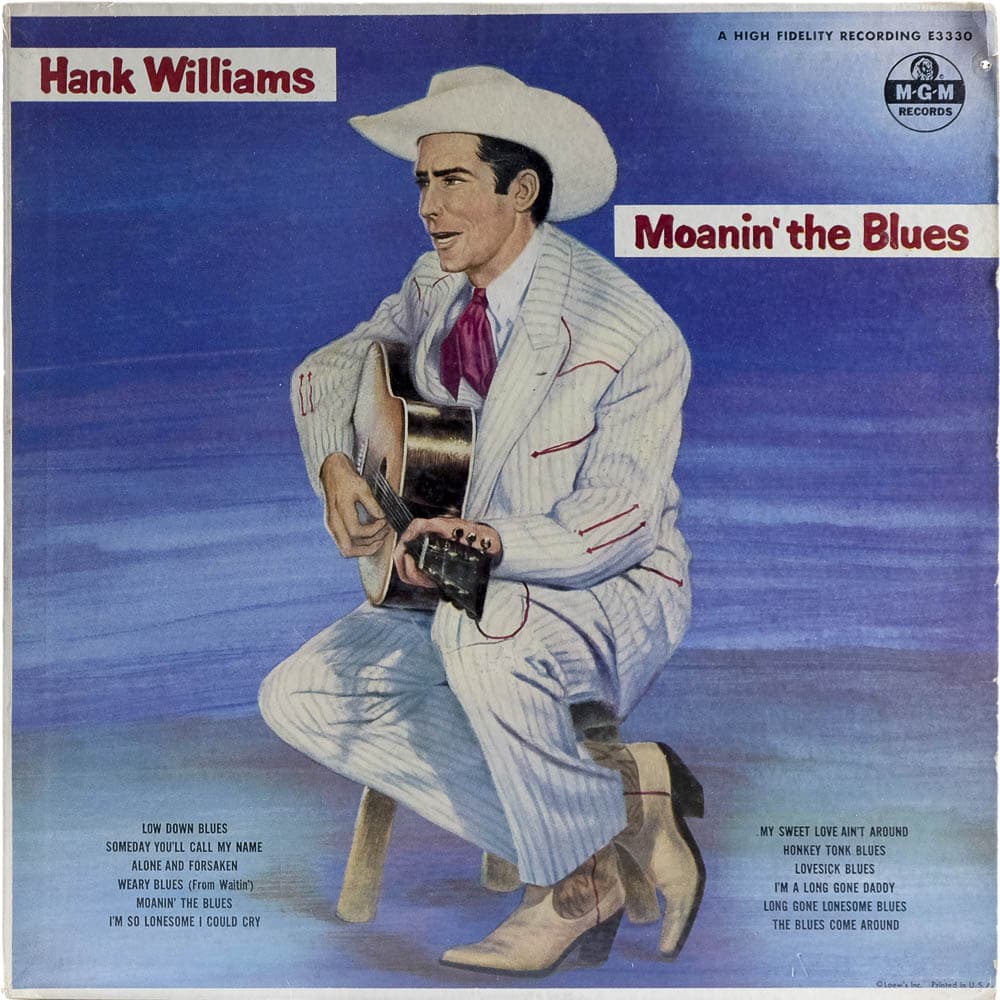

When Hank Williams released “Moanin’ the Blues” in 1950, he gave country music one of its most enduring portraits of working-class loneliness. The song rose quickly to No. 1 on the Billboard Country & Western Best Sellers chart, where it remained at the top for multiple weeks, confirming Williams not just as a hitmaker, but as the clearest emotional voice of his generation. This was not a crossover novelty or a polished pop experiment. It was country music speaking plainly, directly, and without apology.

Written solely by Hank Williams, “Moanin’ the Blues” feels less like a composition and more like a confession overheard. From its opening line, the song drops the listener into a familiar scene: a man sitting alone, money gone, love absent, staring at the clock and waiting for the night to pass. There is no storyline to resolve, no moral lesson to deliver. The song exists entirely within a feeling and that feeling is exhaustion.

By 1950, Hank Williams was already becoming a defining figure in American music. His songs did not rely on metaphor or clever wordplay. Instead, he used simple language to describe complex emotions, trusting that truth did not need decoration. In “Moanin’ the Blues,” this approach reaches near perfection. The lyrics are spare, almost conversational, yet every line carries weight. Anyone who has ever felt left behind by love or circumstance recognizes themselves instantly.

Musically, the song is built on a steady, blues-influenced shuffle, reflecting Williams’ deep connection to African American blues traditions as well as rural white folk music. This fusion was crucial. Hank Williams did not imitate the blues he translated it into country language. The result was a sound that felt both familiar and new, grounded in tradition yet emotionally raw in a way that few country songs had dared before.

Williams’ vocal performance is central to the song’s power. His voice is thin, nasal, and unmistakably human. There is no attempt to hide fatigue or sadness. He sings as if he is already tired of explaining himself. The slight drag in his phrasing mirrors the weariness of the narrator, making the song feel lived-in rather than performed. This honesty is what separated Hank Williams from many of his contemporaries. He did not sing about pain—he sang from inside it.

In the context of post-war America, “Moanin’ the Blues” resonated deeply. The country was changing. Prosperity was uneven, work was hard, and emotional isolation was common, especially for those far from the optimism portrayed in popular culture. Williams gave voice to people who felt invisible. The song did not promise escape or redemption. It simply acknowledged reality and that acknowledgment was enough.

The success of “Moanin’ the Blues” helped solidify Hank Williams’ role as a cornerstone of modern country music. It demonstrated that a song did not need a happy ending to succeed. It only needed to be true. Future generations from George Jones to Johnny Cash would build entire careers on the emotional foundation Williams laid here.

Decades later, the song remains strikingly relevant. Its setting may be a jukebox and a barroom, but its emotional core is timeless. Loneliness does not belong to any era. Neither does honesty. That is why “Moanin’ the Blues” still feels alive because it speaks in a voice that never pretended to be anything other than what it was.

In the end, Hank Williams does not resolve his sorrow. He sits with it. He names it. He lets it exist. And in doing so, he turns private pain into shared experience. That is the quiet miracle of “Moanin’ the Blues” a song that never raises its voice, yet continues to be heard.