A Barroom Tragedy of Pride and Regret: When Love Walks Out the Door

When Kenny Rogers released “Lucille” in 1977, the song did not arrive quietly. It entered the American consciousness like a short story set to music direct, conversational, and devastating in its simplicity. Within weeks, it became a defining moment not only for Rogers’ career, but for modern country storytelling itself. “Lucille” reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, crossed over to No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100, and climbed to No. 1 in several international markets, including Canada. For a country song built almost entirely on dialogue and moral consequence, this was extraordinary.

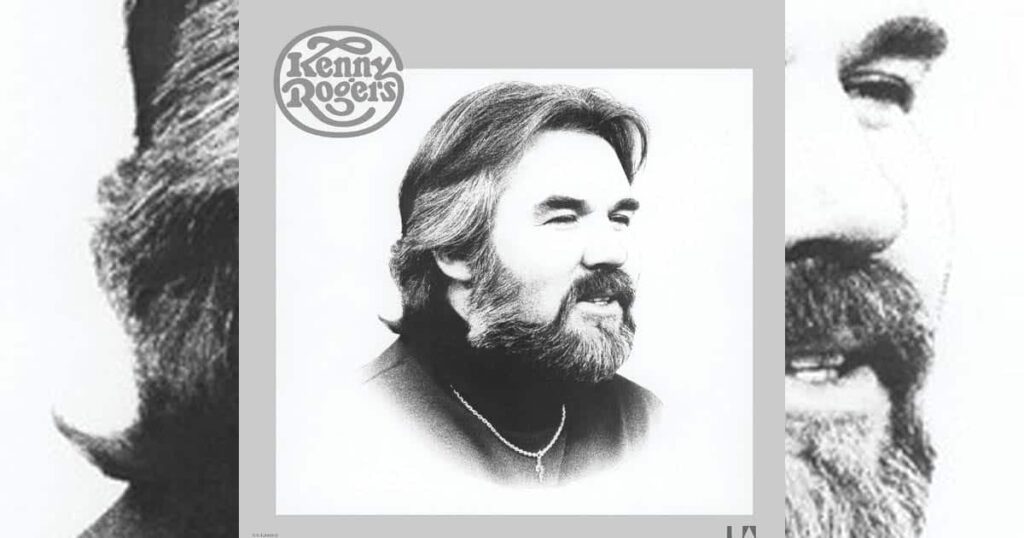

At the time, Kenny Rogers was already a seasoned performer, but he was still in the process of reinventing himself as a solo artist with a deeper, narrative-driven voice. “Lucille” written by Hal Bynum and Roger Bowling became the song that crystallized that transformation. It presented Rogers not as a flashy singer, but as a calm observer of human weakness, someone who understood silence as well as sound.

The story unfolds in a bar, one of the oldest and most honest settings in country music. A man meets a woman named Lucille, recently married, clearly unhappy. Over drinks and conversation, she explains her dissatisfaction dreams deferred, romance faded, promises broken by time and routine. When she abruptly leaves, the man is left not with heartbreak, but with a realization. He looks inward. The song’s most famous line “You picked a fine time to leave me, Lucille” is not directed at the woman in the bar, but at his own wife, waiting at home with children and responsibilities he has taken for granted.

What makes “Lucille” so powerful is its restraint. There is no shouting, no dramatic confrontation. Kenny Rogers sings in a measured, almost conversational tone, allowing the listener to step into the narrator’s conscience. His voice carries weariness rather than anger, recognition rather than blame. It is the sound of a man seeing himself clearly for the first time and not liking what he sees.

Musically, the arrangement is sparse and deliberate. The steady rhythm mirrors the slow turning of thought, while the melody stays close to the ground, never reaching for sentimentality. This gives the lyrics room to breathe. Each word lands with weight, especially for those who have lived long enough to understand how easily love can erode when attention is withdrawn.

In the broader context of 1970s country music, “Lucille” marked a shift. It proved that country songs could be mature without being moralistic, emotional without being melodramatic. It spoke directly to adults who understood marriage not as a fairy tale, but as a daily choice one that can be neglected, sometimes fatally.

For Kenny Rogers, the success of “Lucille” opened the door to a remarkable run of story-driven classics. But none quite captured the shock of recognition that this song delivered. It did not offer redemption. It offered awareness. And for many listeners, that was more unsettling and more honest.

Decades later, “Lucille” still resonates because it does not age. Pride, distraction, emotional absence these are not bound to any era. The song remains a quiet warning, delivered without judgment, reminding us that love rarely ends in one dramatic moment. More often, it fades while we are looking elsewhere.