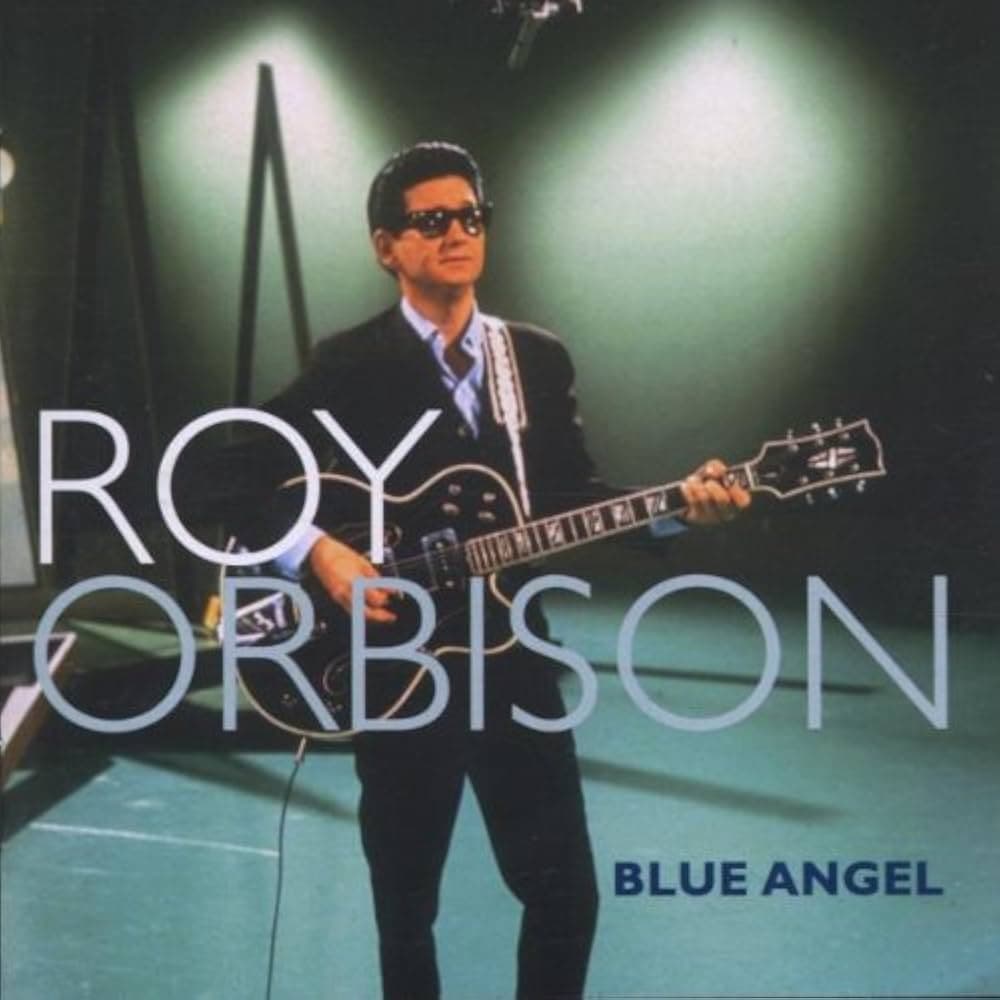

A fragile confession bathed in shadows, where vulnerability becomes strength under a single, unforgiving spotlight

When Roy Orbison sang “Blue Angel” during Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night in 1987, the moment felt like a quiet reckoning with his own past. This was not merely a revival of an early song; it was a conversation across decades. Stripped of youthful urgency and delivered with the gravity of experience, “Blue Angel” emerged as something deeper — a reminder that some emotions do not fade with time, they simply learn how to speak more softly.

“Blue Angel” was originally released in 1960 as a single on Monument Records, written by Roy Orbison and Joe Melson, the songwriting partnership that would later give the world classics such as “Only the Lonely” and “Crying.” Upon its release, the song reached No. 59 on the Billboard Hot 100, a modest showing compared to Orbison’s later chart-toppers. Yet even then, it hinted at something unusual. This was not a conventional rock-and-roll love song. It was introspective, emotionally exposed, and slightly unguarded — qualities that would soon define Orbison’s greatest work.

The song’s narrative is deceptively simple: a man recognizes that the woman he loves is out of reach, almost otherworldly. Calling her a “blue angel,” he elevates her beyond the human realm, suggesting beauty, distance, and sorrow all at once. The color blue carries its familiar weight — sadness, longing, emotional depth — while “angel” implies purity and unattainability. The singer does not demand her love; he merely confesses his devotion, knowing it may never be returned. Even in its original form, “Blue Angel” carried the seeds of Orbison’s lifelong themes: longing without bitterness, heartbreak without blame.

By the time of Black and White Night, those themes had matured. Recorded on September 30, 1987, at the Ambassador Hotel’s Coconut Grove in Los Angeles, the concert captured Roy Orbison surrounded by an extraordinary group of admirers — Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, k.d. lang, and others — all standing slightly behind him, almost reverently. Yet during “Blue Angel,” it feels as if he is entirely alone, suspended in that pool of black-and-white light.

Vocally, this performance is a masterclass in restraint. Orbison does not reach for drama; he allows it to rise naturally from the melody. His voice, still remarkably pure, carries a subtle fragility that was less apparent in 1960. Each note feels weighed, considered, as if shaped by years of living with the emotions the song describes. There is no attempt to modernize the arrangement. The song remains simple, honoring its origins, but the emotional context has changed completely.

What makes this version so powerful is the contrast between past and present. The young Orbison who first recorded “Blue Angel” was still searching for his voice, experimenting with vulnerability in a musical world that often rewarded bravado. The Orbison of 1987 no longer needed to prove anything. Loss, love, tragedy, and triumph had all passed through his life, and they linger in the tone of his delivery. The song becomes less about romantic yearning and more about acceptance — the quiet understanding that some loves exist only to be felt, not fulfilled.

Visually, Black and White Night reinforces this emotional clarity. The absence of color removes distraction. There are no elaborate stage effects, no spectacle. Just a man, his guitar, and a voice that seems to come from somewhere deeper than performance. The audience response is restrained but attentive, as though aware they are witnessing something intimate rather than entertaining.

In the broader arc of Roy Orbison’s career, “Blue Angel” occupies a special place. It is not among his biggest hits, yet it foreshadows everything that would make him timeless. In this late-career performance, the song feels complete at last — as if it had been waiting decades to be sung this way.

Long after the final note fades, “Blue Angel” remains suspended in memory, delicate and unresolved. In the hands of Roy Orbison, it becomes a testament to the idea that true emotional honesty never goes out of style. Some songs do not age; they simply grow wiser.