A Voice Behind the Walls, Where Truth, Guilt, and Freedom Collide

When Johnny Cash performed “Folsom Prison Blues” live at San Quentin Prison in 1969, he was not revisiting a familiar hit—he was completing a circle. This performance stands as one of the most powerful moments in live recording history, where song, setting, and singer merged into a single act of truth-telling. With clear sound quality and an audience that understood every word not as metaphor but as lived reality, “Folsom Prison Blues (Live at San Quentin)” became more than music. It became testimony.

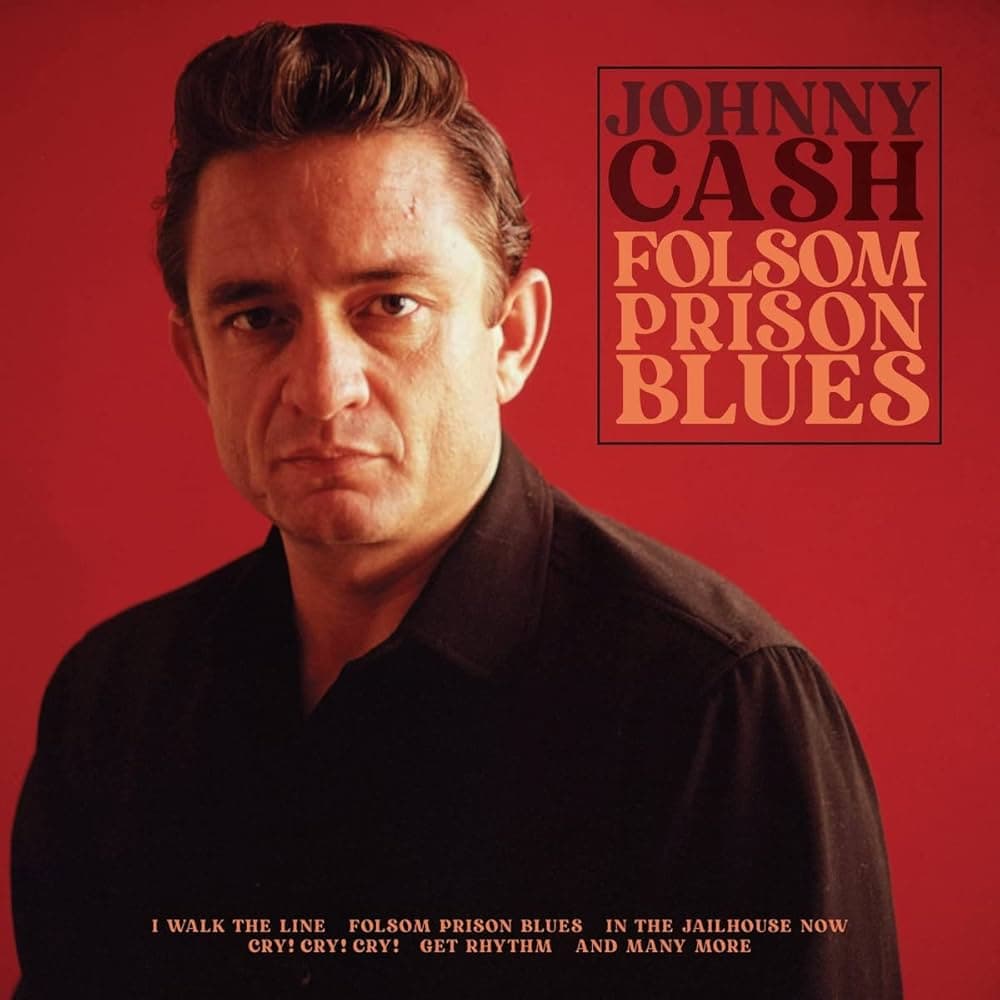

Originally written by Johnny Cash in 1955, “Folsom Prison Blues” was inspired in part by Gordon Jenkins’ song “Crescent City Blues” and by Cash’s own fascination with prisons, guilt, and moral consequence. The studio version was released on the album Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar! in 1957, helping establish Cash’s stark, rhythmic sound. While the original single did not dominate the pop charts, it became one of his signature songs and laid the foundation for his lifelong artistic engagement with themes of incarceration and redemption.

The song reached its full cultural weight through live performance. Cash’s first prison concert album, At Folsom Prison (1968), turned “Folsom Prison Blues” into a national sensation, with the live single reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart and No. 32 on the Billboard Hot 100. One year later, Cash returned to a harsher, more volatile setting: San Quentin Prison. The resulting album, At San Quentin, released in 1969, captured a rawer, more confrontational atmosphere—and nowhere is that clearer than in “Folsom Prison Blues.”

From the opening line—“I hear the train a-comin’”—the room responds. This is not polite applause. It is recognition. At San Quentin, Cash sings to men who do not imagine confinement; they live it. When he delivers the infamous line “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” the reaction is explosive, not because it glorifies violence, but because it speaks plainly about consequence. Cash never softens the line, never explains it away. He lets it stand, heavy and unresolved.

Musically, the performance is lean and relentless. The boom-chicka-boom rhythm drives forward like the train in the lyrics—unforgiving, unstoppable. Cash’s voice is firm, steady, and direct, carrying authority without arrogance. The good sound quality of this recording allows every detail to be heard: the snap of the snare, the pulse of the bass, the tension in Cash’s phrasing. Nothing is buried. Nothing is hidden.

What sets this performance apart is Cash’s emotional posture. He does not sing about prisoners; he sings with them. There is no condescension, no romanticization. Cash never claims innocence, nor does he pretend to share their fate. Instead, he acknowledges a shared human flaw—the capacity for wrongdoing, regret, and longing. That honesty earns trust, and trust is what fills the room.

The meaning of “Folsom Prison Blues” deepens in this setting. It is not a protest song in the traditional sense, nor a plea for sympathy. It is a reflection on confinement in all its forms—physical, moral, psychological. The train represents freedom, but also distance: a life moving forward without the narrator. Cash sings this not as fantasy, but as loss.

Within At San Quentin, the song stands alongside other confrontational moments, including the title track “San Quentin,” which openly challenges the prison system. Yet “Folsom Prison Blues” remains the emotional anchor. It reminds listeners that the system is made up of individuals, each carrying their own regrets and memories.

Over time, this performance has come to symbolize Johnny Cash’s role as a moral witness in American music. He did not offer easy answers. He offered presence. By bringing his music into places most performers avoided, he gave voice to those rarely heard—and did so without dilution or sentimentality.

Listening today, “Folsom Prison Blues (Live at San Quentin)” remains unsettling, vital, and deeply human. The sound is clear, the message unfiltered. It reminds us that music can cross walls, that truth does not require decoration, and that sometimes the most honest songs are the ones sung where freedom is only imagined.

In the end, this performance endures because it refuses comfort. It asks listeners to sit with consequence, to hear joy and regret in the same breath. Through this song, Johnny Cash did not free anyone—but he acknowledged them. And in doing so, he gave the song, and himself, a place in history that remains unshaken.